When my wife and I began our search for a 1940 Buick Series 90 Limited, little did we know that we would wind up with TWO Buicks. Well, to clarify, there is only one Buick “vehicle” in our garage, but it is a composite of two different cars: the original Buick body and interior, combined with the running gear (engine/transmission/rear axle) from a 1972 Buick Electra. The Buick Electra drivetrain was pretty awesome for its time: 455 cubic inch V8, driving through GM’s TH400 automatic transmission. But more about that later.

We had been looking for a true 1940 limousine (8 passenger seating, thanks to an additional row of pop-up seats in the rear compartment) for quite some time, and found these cars to be extremely rare. From my research, fewer than 1,000 of these models were ever built. Of course, for a certain time period after new, limousines, in particular, get relegated to the “just-another-used-car” category, so many of the special cars eventually became permanently parked out behind the barn, or just turned over to an auto wrecker, so who can say how many of these priceless vehicles are left.. likely in the double digit quantity at most?

Normally I’m a purist when it comes to retaining and restoring a classic car’s original drive train. However, “Roosevelt”, OUR Buick 90 series, was acquired specifically for use commercially in our classic limousine business, so the idea of a more modern drivetrain, with readily obtainable parts, had broad (if, in retrospect, misguided) appeal.

So, one blustery early spring day in 2015, my car retrieval buddy Bill Hayes and I hooked up the trailer and truck, and hit the road to Des Moines to take possession of our new diamond-in-the-rough.

Upon initial inspection, we found the car’s exterior and interior to be in very nice condition, maybe a conservative 8 out of 10 overall. And that first impression, in retrospect, overshadowed a mountain of mechanical problems yet to encounter.

I suppose my initial “test” drive of the car should have been a clue as to what to expect, that the car definitely wasn’t going to be a quick plug-and-play acquisition. First, I discovered the brakes to be grossly over-sensitive, such that the lightest touch would almost instantly lock up the front wheels. In addition, at the conclusion of our 3 mile or so drive (on a very cool day), as we pulled back in the parking lot, steam started coming out of the cooling system. The seller deftly pointed out that the radiator cap had been left off, so we accepted that as a quick solution, loaded up the huge machine onto our trailer, and headed south to Austin.

Little did I realize at the time that it would be fully 6 weeks later before the old boat was considered safe to venture outside our shop!

First up, there were a number of interior function and appearance issues that I felt had to be addressed before the car was ready for the public.

The previous owner’s transplant of 1972 Buick mechanicals included installation of that donor car’s steering column and power steering and power brake systems. Unfortunately, that included the gawdawful 70’s plastic steering wheel (including tilt mechanism.. something I’ve never been fond of in a vintage car) THAT had to go, and pronto!:

I thought about trying to source an original ’40’s Buick steering wheel, but those are scarce, and in restored condition command about the same price as a small used Honda (besides, such a steering wheel wouldn’t easily mate with that 70’s steering column).

I finally had to settle on a period style “banjo” steering wheel, which I sprayed an ivory color to emulate the original colors as best I could, using automotive quality base coat/clear coat.

A more glaring issue was the complete absence of the original radio. Instead, just a big hole was left in the dash, accented by the ugly black plastic control panel and knobs of the Vintage Air A/C system the owner had installed (sort of).

There were no vents installed for the A/C either.. the owner had just wired the ducts under the dashboard, pointed to blow cold air on your feet! Additionally, none of the original gauges were connected. Since the oil pressure and temperature gauge were originally mechanical, I reluctantly decided to just go with after-market gauges, and determined that the only reasonable way to deal that gaping hole left by the missing radio was to just fabricate a complete under-dash panel using a sheet of engine turned aluminum to house the A/C vents, gauges, headlight switch, and air conditioner switches. All of the switchgear knobs were replaced with matching, turned billet aluminum knobs.

The original Buick glove box and gauge panel sported a simulated engine-turned metal pattern as well, but had been painted on this car. I had them both chrome plated, bringing the entire dash more in tune with its origin:

The wiring was a nightmare as well. The mechanical transplant had included use of the complete engine and dash wiring harness from the donor ’72 Buick. In some respects this was a good thing, as it did eliminate the 75 year old crumbling original wiring. Unfortunately though, the project under the previous owner had not progressed beyond basic hook up of the engine for minimum functionality. No turn signals, horn, interior lights, gas gauge, high beam indicator, ammeter, warning lights.. the list went on and on. And, the underdash wiring was just a nightmare:

The good news? Wiring diagrams were available online for the ’72 Buick, and they were good, complete, detailed, and properly color coded. Utilizing those diagrams combined with the fairly complete stock wiring illustration from the 1940 Buick shop manual (needed to merge the ’72 harness from the front with the ’40 Buick chassis harness servicing the rear of the car), I was able to slowly piece together the puzzle, and after several weeks, had successfully restored all the functionality of the electrical components.

The original vacuum powered wiper motor was still installed under the dash, but not connected to anything, nor were there wiper arms at all. After testing the vacuum motor and finding it had limited functionality, I decided to opt for installing a universal 2-speed electric wiper motor. Then I sourced new after market wiper transmission towers and blades, designed specifically for a late 40’s Chevrolet, but was able to modify the drive mechanism to function properly with the new wiper motor.

The original stock speedometer appeared to be functional, but there was no cable at all from the transmission. Miraculously, because of the ubiquity of GM’s TH400 automatic transmission installed in the car, I found a knowledgeable company that was able to fabricate a speedometer cable with correct fittings on each end, AND to provide a drive gear at the transmission to insure accuracy of the speed indication. I lubricated the speedometer, connected the cable, and sure enough, it worked great, and showed accurate indications throughout the normal operating range!

Next, I had to address the issue of seat belts, as the car came with none installed. That’s right, all 8 seating positions needed seatbelts. Accomplishing this task for the front seat was no cakewalk. It seems that all the GM cars of this period had front seats with the upper and lower sections joined with a sold piece of metal. There is absolutely no place to slip a seat belt between the upper and lower segments. Therefore, I had to remove the huge single-piece, refrigerator-size-and-weight seat from the car, disassemble part of the upholstery to gain access to the joined sections, then cut holes in the metal to allow a pass-through space for the belts:

\

\

Installing belts for the pop-up second row of seats in the aft compartment also posed a problem.

I didn’t anticipate using those additional seats often, instead keeping them folded into their recess. This meant the seat belts would be laying on the floor, to be trampled on by passengers in the rear.

I finally was able to source belts that connect and disconnect easily to eye bolts that stay permanently in the floor, so that the belts can be removed when not in use.

The original clock, installed in the center of the glove box door, was in beautiful physical condition, but of course didn’t operate. I sent it off to a vintage clock repair place, got quick turn around, and now have a nicely functioning clock in place.

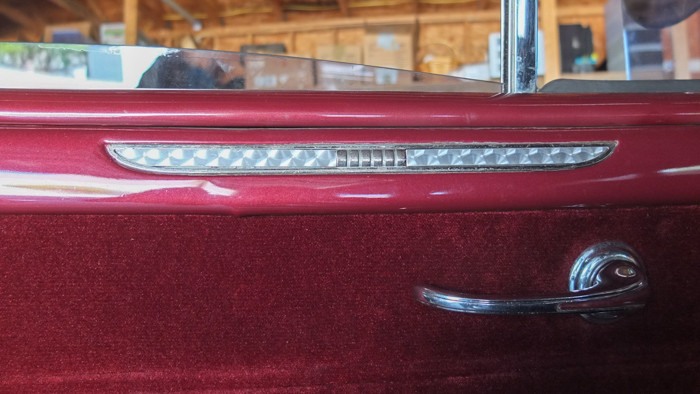

Finally, to complete the interior, I discovered that the original plastic inserts in the trim medallions on each door’s window trim had long since deteriorated, leaving just the outer shell:

Using the same turned aluminum material I had used for the under-dash panel, I fabricated new inserts and secured them into place:

All the work described above was completed before I ever drove the car out of the workshop. But finally, with functioning gauges, lights, and instruments, it was time to take the old babe out on the road. That’s when I learned my Buick Series 90 Limited “commissioning” task was just beginning!

to be continued next month …

Leave a reply